Are we truly introverts or just socially and emotionally undeveloped? Here’s how I came to learn that truth about myself, how it’s changed the way I think about making software, and why if you make software Sherry Turkle’s “Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age” is a must-read. If you’ve ever thought, “I’d rather text than talk”, this is for you.

I’ve long considered myself an introvert. If you’re a designer or programmer, a self-proclaimed geek, a computer enthusiast — if you live on the web — you may think so, too. Perhaps this sounds familiar: I was content to play alone as a kid spending hours building with Lego, lost in my imagination. I made art, read books, and was fascinated by computers.

The computer would do amazing things if I could master its secret language of esoteric syntax. It was absorbing and stimulated the mind. Predictable and consistent, never doing any more or less than instructed.

Unlike people. They were messy and inefficient and cared about the most trivial things! I wasn’t without friends but my tribe mostly cared about the same things I did. When we did get together it was often to share techniques and experiences from our time in solitary activities. Instead of being intertwined by friendship we journeyed through life in parallel. The things we were passionate about made no sense to adults. They didn’t advance our social standing or impress the girls. So we retreated further.

It wasn’t until the internet arrived that it all suddenly made sense. I remember distinctly in college and in my first job after college the elation to learn that I could be paid to indulge in all the things I was already doing. I was able to work with computers all day long, figuring things out, reading, making, building, tinkering. The internet was wide open and seemingly crafted especially for us geeks. You didn’t even have to take a class — everything you needed to know to make things on the internet was on the internet.

Building the case for introversion

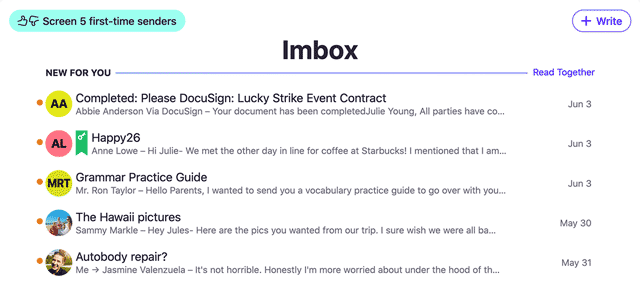

Not only did the web allow me to get paid for work I’d have done for fun but it helped me to connect with other people just like me. We worked and communicated through the web. Email and IM meant no one had to comb their hair, put on pants, make small talk, or stand in the corner while the extroverts had all the fun. Asynchronous communication was efficient and transactional. I didn’t have to ask you about your haircut or pets before requesting the information I needed from you. My “friends” were right there, neatly contained in that narrow little window on my screen. There when I need them, minimized when I didn’t.

As we geeks became more essential to the companies we worked for we were coddled. They bent the old rules to make us feel comfortable because we were shy and temperamental. Casual dress codes, unlimited Cokes and foosball tables were standard issue. We were special snowflakes who passed around articles to explain why were were so different and how we should be treated*.

It all came to a head for me a few years ago when I read Susan Cain’s Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. Here was the definitive apologetic I’d been waiting for. I didn’t need to feel bad for being awkward, for preferring emails to phone calls, for wanting to stay in rather than go out — it was just how I was. Here introversion was presented as an advantage, not something to be ashamed of. Damn the extrovert agenda!

Whoever you are, bear in mind that appearance is not reality. Some people act like extroverts, but the effort costs them energy, authenticity, and even physical health. Others seem aloof or self-contained, but their inner landscapes are rich and full of drama. So the next time you see a person with a composed face and a soft voice, remember that inside her mind she might be solving an equation, composing a sonnet, designing a hat. She might, that is, be deploying the powers of quiet.

Years ago when I first joined 37signals I was overjoyed at having found an introvert’s dream job. Here I could work from my home hiding behind a computer nearly 100% of the time. Not working in an office meant nobody to drop by for small talk or force me to speak in front of a crowd. Customer support? Email. Meetings? Toxic. We only got together in-person a few times a year.

I remember those in-person meetings reinforced my self-diagnosis. Sitting around the conference table, the ideas and options came fast and furious. I could hardly get in a word. My coworkers wanted to work out the design now, iterating on a whiteboard in REAL TIME! What I wanted to do was take in all the information, go home and work it out in solitude, at the computer. I knew I could think as creatively as anyone else but I needed to do it on my terms.

Why take the risk of sharing a possibly stupid idea off-the-cuff when I could retreat to my cave and craft a perfectly edited proposal or iterate on a polished design in solitude?

Cain’s book validated all of this. I didn’t need to feel bad, this is just how I was and I needed to assert myself such that I could work on my terms. The book even stresses, “Don’t think of introversion as something that needs to be cured”. So I didn’t look to change, I just kept justifying. Is there anything we’re better at than justifying our faults and failures? And the internet makes it all too easy to follow only the people who agree with us and read only what represents our worldview. I may be a weirdo, but there are thousands of people who are just as weird.

Now my point is not to deride Cain’s book (which is very good) or somehow deny introversion. There is no question that introversion is real and many, many people are wired this way. If you think you might be, “Quiet” is a great read. The problem for me is as great as the book made me feel about my behavior, I don’t think I was actually an introvert.

Introverts are easily overwhelmed by too much stimulation from social gatherings and engagement, introversion having even been defined by some in terms of a preference for a quiet, more minimally stimulating external environment.

Extraverts are energized and thrive off of being around other people. They take pleasure in activities that involve large social gatherings, such as parties, community activities, public demonstrations, and business or political groups. They also tend to work well in groups. An extraverted person is likely to enjoy time spent with people and find less reward in time spent alone. They tend to be energized when around other people, and they are more prone to boredom when they are by themselves.

— Extraversion and introversion

I didn’t dislike social gatherings and didn’t need to balance social time with solitude in order to recharge as is commonly said of introverts. Some of the best times of my life were in social settings. I couldn’t think of any time with my computer that would crack the top ten. I wasn’t sure what to do. Introversion justified my behavior but the more clinical definitions left me with questions.

Discovery

It was only recently, years later, in divorce and another book that I found an answer. Divorce viciously unmasked my self-deception. Covering my social and emotional deficiencies in the echo-chamber of the internet and the apologetics of introversion made me feel better but it let the problems fester. In losing everything I was forced to turn to real people for healing. First in the few relationships I had left, later in seeking and forming new ones. I could have stayed home continuing to wrap myself in the comfort of the misunderstood introvert. Instead I sought change. Forming new relationships and asking for help required a humility and vulnerability I’d never thought possible but offered rewards beyond imagination.

Being comfortable with our vulnerabilities is central to our happiness, our creativity, and even our productivity.

Sherry Turkle’s Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age was the final piece of the puzzle. It’s a rather damning look at how the way we communicate in the smart phone era is killing real, face-to-face conversations in our friendships, families, schools and workplaces and what we’re losing when that happens.

We’ve gotten used to being connected all the time, but we have found ways around conversation — at least from conversation that is open-ended and spontaneous, in which we play with ideas and allow ourselves to be fully present and vulnerable. But it is in this type of conversation — where we learn to make eye contact, to become aware of another person’s posture and tone, to comfort one another and respectfully challenge one another — that empathy and intimacy flourish. In these conversations, we learn who we are.

— Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age

The book is particularly focused on a population who have never developed the skills to truly have a conversation in “real time” and how that’s destroying empathy (sound familiar?). How social media offers the unrealistic promise of connecting without giving anything of ourselves. How the ways we’ve become wired to avoid boredom at all costs — stimulation is just a tap away — has assaulted our ability to be secure in solitude, rest our minds, and open them to the serendipity and creativity that comes from unstructured reflection. How even the presence of a phone on the table changes the depth and nature of a conversation.

In seeking productivity and efficiency we’re turning conversations into, as Turkle’s puts it, merely “transactional” exchanges of information. We’re treating people like apps that we tap when we need stimulation, close when we’re bored, switch away from when something more interesting comes around and delete when they no longer offer anything in the transaction.

What does this have to do with software?

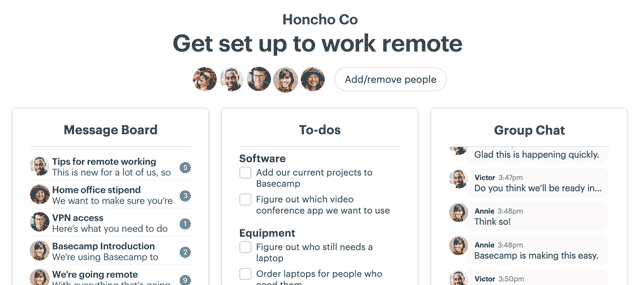

At Basecamp we make software that helps people communicate, get work done and stay connected. Millions of people use it to increase their productivity enabling them to work when, where and how they want. It works on Macs, PCs, iOS and Android, phones and tablets. It notifies you when a task is due, a meeting is starting or someone needs your attention — anywhere in the world, any time of day. I’m proud to help make a tool that helps so many people get things done but I often worry about the other side. Should I be proud when a mom is using Basecamp instead of watching her kid’s soccer game? Who’s fault is it when dad comes home from work on-time but isn’t really present because Basecamp keeping pinging his phone all evening? Every time Basecamp sends a notification should I wonder if it’s helping someone be a better worker or impeding them from being a better person?

The age of the smartphone is here to stay. Well beyond the days of Web 2.0 our industry is making the best software ever seen. Everywhere you look there are beautiful, fast, intelligent apps that allow us all to do more both simultaneously and cumulatively. We’ve had tremendous success in making people more productive but what have we gained? Do we have more free time? More leisure? No! As Turkle aptly puts it, “We are living moments of more and lives of less.”

Reclaiming Conversation ends with a call to make software that has moved beyond mere productivity and thinks about the human on the other side. Can we make apps that are less-sticky, less addictive, that reward users for completing a focused task then quitting rather than enticing them with something else? Can apps encourage uni-tasking? Can they help users take back their time?

I’m proud to work for a company that’s starting to ask these hard questions and seeking real answers. Basecamp’s Work Can Wait feature let’s users create a clear separation between when they’re working and when they don’t want to be bothered with work—even on mobile devices. This is a great step forward. Granted, many apps and operating systems have recently incorporated similar features the help us manage the noise but the future is here when computers are proactively helping us be more human, not less.

Reclaiming Conversation has completely changed the way I think about people, computers, social media, and designing software. If you’re a parent, a co-worker, or a friend; if you’re dating or married; if you’re a boss; if you make apps; if you’ve ever thought, “I’d rather text than talk”, this book is a must-read. It’ll make you think about the way you use software, the ways software can use you, and what you’re losing every time you glance at your phone. Our industry may truly be full of introverts, but I suspect that at least some of you are like me, not realizing how you’ve let these tools change you. I hope I’ve made you curious enough to find out. If you make software, I hope you’re inspired to help your users find balance, too.

Visit Basecamp.com to learn more about the all new Basecamp 3, try it for free and start living like Work Can Wait.