If you want to understand why so many startups become infected with unhealthy work habits, or outright workaholism, a good place to start your examination is in the attitudes of their venture capital investors.

Consider this Twitter thread involving two famous VCs, Keith Rabois and Mark Suster:

These sentiments are hardly aberrations. There’s an ingrained mythology around startups that not only celebrates burn-out efforts, but damn well requires it. It’s the logical outcome of trying to compress a lifetime’s worth of work into the abbreviated timeline of a venture fund.

It’s not hard to understand why such a mythology serves the interest of money men who spread their bets wide and only succeed when unicorns emerge. Of course they’re going to desire fairytale sacrifices. There’s little to no consequence to them if the many fall by the wayside, spent to completion trying to hit that home run. Make me rich or die tryin’.

The entrepreneurs who sign up for such pressures may have asked for it. If you, knowing their sentiments, ask Rabois or Suster for millions to fund your venture, then you probably should expect to have your vacations, weekends, hobbies, family time, or outings with the kids questioned.

But the pressures don’t stop with the person who signs the term sheet. That shit trickles down. In fact, it’s likely to amplify as it rolls down the hill, like a snowball gathering mass. Because once the millions have cleared, and the headcount has been boosted, it’s usually other people who actually have to make good on those exponential expectations.

The sly entrepreneur seeks to cajole their employees with carrots. Organic, locally-sourced ones, delightfully prepared by a master chef, of course. In the office. Along with all the other pampering and indulgent spoils AT THE OFFICE. The game is to make it appear as though employees choose this life for themselves, that they just love spending all their waking (and in some cases, even sleeping) hours at that damn office.

And if the soma-like inducements don’t work, there’s always the lofty talk about THE MISSION: We’re not just here to capture more attention or steal more privacy in the name of advertising, no, we’re connecting the world! Your single-track life has meaning! All your sacrifices are for a greater good!

Yeah, right.

Not only are these sacrifices statistically overwhelmingly likely to be in vain, they’re also completely disproportionate. The programmer or designer or writer or even manager that gives up their life for a 80+ hour moonshot will comparably-speaking be compensated in bananas, even if their lottery coupon should line up. The lion’s share will go to the Scar and his hyenas, not the monkeys.

And yet so many continue to go along, because they already went this far. Sunk cost is an easy theoretical concept, but it’s devilishly hard to put in practice. Which is why the yoke of the four-year vesting cliff, the short-exercise window for options, and all the other tricks and techniques employed by cap table-designing masters are so effective. Once the hook is in, the line and the sinker follows easily.

But it will be in spite of prevailing evidence on the power of sleep, recuperation, and sustainable work habits. Whether you’re a top-flight basketball player, like Kobe Bryant, whose off-season work schedule is limited to just six hours per day:

The Kobe Bryant workout routine features a hefty mix of track work, basketball skills and weightlifting. His off-season workout has been called the 666 program because he spends 2 hours running, 2 hours on basketball, and 2 hours weightlifting (for a total of 6 hours a day, six times a week, for six months).

Or his competitor, LeBron James, who frequently gets 12 hours of sleep. Or any of the other star athletes who prioritize their sleep and recuperation as a key component of their performance:

Since athletes need more sleep than average people, eight to 10 hours of zzz’s a night is recommended, and that’s not just before game day — that’s every evening. After all, the more often and more vigorously you use your muscles, the more time it takes for your body to repair and rebuild them. Roger Federer and LeBron James famously snooze for an average of 12 hours a night, while Usain Bolt, Venus Williams, Maria Sharapova, and Steve Nash get up to 10 hours a night. Federer has said, “If I don’t sleep 11 to 12 hours per day, it’s not right.

Or how about prodigious thinkers and writers, like Trollope, Dickens, or Darwin who all sought to complete their work within fixed, modest slices of the day, and then kept the rest for leisure. Here’s Darwin’s routine:

After his morning walk and breakfast, Darwin was in his study by 8 and worked a steady hour and a half. At 9:30 he would read the morning mail and write letters. At 10:30, Darwin returned to more serious work, sometimes moving to his aviary, greenhouse, or one of several other buildings where he conducted his experiments. By noon, he would declare, “I’ve done a good day’s work,” and set out on a long walk on the Sandwalk, a path he had laid out not long after buying Down House. (Part of the Sandwalk ran through land leased to Darwin by the Lubbock family.)

When he returned after an hour or more, Darwin had lunch and answered more letters. At 3 he would retire for a nap; an hour later he would arise, take another walk around the Sandwalk, then return to his study until 5:30, when he would join his wife, Emma, and their family for dinner. On this schedule he wrote 19 books, including technical volumes on climbing plants, barnacles, and other subjects; the controversial Descent of Man; and The Origin of Species, probably the single most famous book in the history of science, and a book that still affects the way we think about nature and ourselves.

Neither these athletes or these writers were giving up anything on whatever contemporaries that may have put in more time, more hours, or greater sacrifices. Their contributions to the world were in no way diminished by their balanced approach, quite the contrary.

So don’t tell me that there’s something uniquely demanding about building yet another fucking startup that dwarfs the accomplishments of The Origin of Species or winning five championship rings. It’s bullshit. Extractive, counterproductive bullshit peddled by people who either need a narrative to explain their personal sacrifices and regrets or who are in a position to treat the lives and wellbeing of others like cannon fodder.

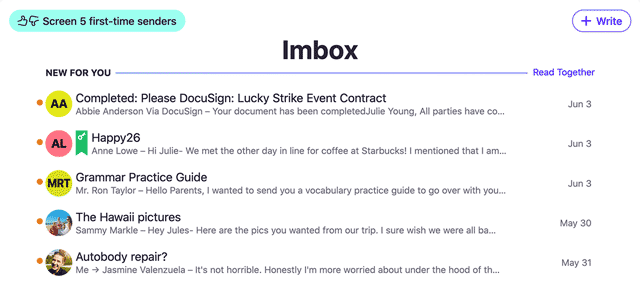

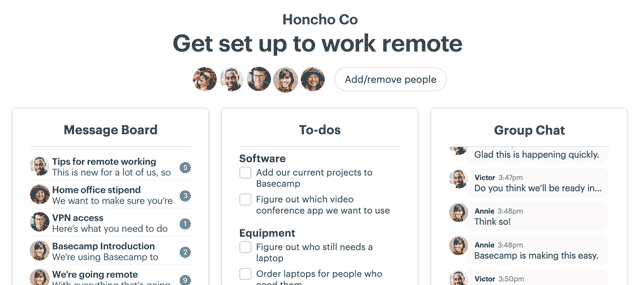

Finally, as way of having my own skin in the game, we’ve been running a wonderfully successful business at Basecamp for some fourteen years now. One profitable since the get-go without demanding the total consumption of life force from the people working here. Neither from Jason nor I, nor from our employees.

Hell, right now, we’re working our four-day summer weeks until the end of August. This while servicing over a hundred thousand paying customers, stewarding Ruby on Rails, writing a new book, and ranting with a fervor against the extractive logic of many a venture capitalist. Forty hours or less has been plenty to do all of that since the beginning, and it’s likely to be plenty for you too.

Workaholism is a disease. We need treatment and coping advice for those afflicted, not cheerleaders for their misery.

If the ways of venture capital has you thinking there’s gotta be another way, then I invite you to read RECONSIDER and Exponential growth devours and corrupts. The alternative path exists.

Great piece, but it’s not just startups. This insanity has been pervasive and celebrated at even the largest and oldest tech companies for the last 15 years. I’ll write my story someday.