Recovering from the paralysis of burnout

Take a moment and imagine: what if you could only smile with half of your face?

In fact, give it a try. Relax the left side of your face, and smile — really, really smile — with the right side. Imagine you’ve just heard something hilarious, or wonderful. Show some teeth! But only on the right side. You might want to put a hand on your left cheek to make sure you’re not moving any muscles there.

Feels kind of goofy, doesn’t it? Awkward, and unnatural.

Now. Imagine that this was your actual smile. How would it affect your interactions with people? How would it affect your self-image?

How would it affect you?

For a few days leading up to January 19th, my tongue tasted like wintergreen.

This was odd. I’d never experienced anything like this before, and while I actually really like wintergreen, having it perpetually on one’s tongue is a bit of a turn-off. I tried brushing my tongue with my toothbrush. I tried mouthwash. I tried everything I could think of, but nothing would remove the odd taste.

I wasn’t too worried. I figured it would wear off eventually, and I’d probably never even remember the episode.

Turns out, I was half right. It would wear off, but I would certainly never forget the experience.

The morning of January 19th, I got up and went about my morning routine, but while I was shaving I noticed something odd. The left side of my face felt like I’d just been to the dentist. Numb, I thought.

Only, that wasn’t right. I could feel it just fine. It was more the loss of control that you feel after being shot full of dental anesthetic. My left cheek, and the lips on the left side of my mouth, were slow. I couldn’t think how else to describe it.

Unlike my wintergreen tongue, this freaked me out. My thoughts immediately went to worst case scenarios. Tumor? Stroke? I visited my doctor as soon as I could, that very morning.

He nodded as I explained the situation to him, listening as I described the facial symptoms as “not a numbness, but more like I can’t move it.”

He nodded once more when I finished, and smiled reassuringly.

“Bell’s palsy!” he told me.

Bell’s palsy…? “Tell me more about that,” I said.

So he did. Apparently there is this thing called the seventh cranial nerve. It starts in the back of the head, and then branches in two. One branch passes through the left inner ear, the other through the right, and from there they run to each side of the face. This nerve controls facial expressions, taste, and the closing (but not opening) of the corresponding eyelid.

All it takes is for something to happen to one of those branches — some kind of trauma, or infection — and those nerve impulses can no longer propagate. Your face stops moving. Your eyelid can’t close. Your sense of taste goes away.

But just on one side.

The doctor assured me it was (almost always!) temporary, and that it would go away in a couple of weeks. He told me to expect it to get worse before it got better, and prescribed some medication which, he said, would speed its recovery.

I swear, this was the weirdest thing to happen to me since puberty.

As promised, it got worse over the next few days, until the left side of my face was completely paralyzed. I would look in the mirror and strain for any motion at all — a twitch, anything! — but it was no use. My face would not move.

What is more, because my left eye wouldn’t close all the way, it watered constantly. I carried tissues with me everywhere and used them to help hold my eye shut. Driving was difficult, because the world looked distinctly moist with an eye full of tears. And at night, I had to sleep with my eye taped shut to keep it from drying out and being damaged.

(Let me tell you, sleeping with one eye taped shut is about as much fun as it sounds.)

I was constantly surprised by all the things I couldn’t do. Eating was difficult, because food kept wanting to dribble out of the paralyzed half of my mouth. I couldn’t whistle at all, which was a significant hardship for a compulsive whistler like myself.

I couldn’t scrunch my eyebrows — trying to felt distinctly odd. I couldn’t roll my tongue, since the left half wouldn’t cooperate. I couldn’t puff my cheeks when the left side of my mouth wouldn’t hold shut. I couldn’t wiggle my left ear, or flex my left nostril. I couldn’t make my “Skeptical Mr. Spock” look, with one eyebrow raised. All the stupid human tricks I knew were utterly useless.

I couldn’t say my “P’s” and “F’s”, either. Try it: put the tip of one finger in the left corner of your mouth, and try to say something like “fluffy puppy.” This was especially problematic as I was currently reading “The Lord of the Rings” to my eight-year-old. Just you try saying “Frodo” and “Pippin” with half your mouth misbehaving!

And most devastating of all, I couldn’t smile. Leastwise, I couldn’t smile fully. My most sincere smile felt unnatural, forced, and ugly.

I tried to make the most of it. I tried to laugh at the weirdness of it all. My kids loved it when I would say it was my “SUPER FACE!” (Remember, my “P’s” and “F’s” were ridiculously plosive.) I tried to joke, and be patient with the entire experience.

But I was profoundly affected by being unable to smile. I felt trapped behind my eyes, unable to really express what I was feeling. I was brought face-to-face with depression, something I’d never really battled before.

On January 30th — eleven days after my initial diagnosis — I discovered that I could twitch the muscles at the corner of my mouth. Just the tiniest bit, but it felt like a marvelous victory! By the 4th of February, I could produce an airy whistle, and immediately began putting it to good use. By the 7th, my face was at about 50% of its original function.

And by the 14th, I was ready to declare myself officially healed.

The experience had passed, but I had been deeply affected. It had touched me far more profoundly than I would ever have expected. I was a different person than I had been just four weeks before.

And I could smile again.

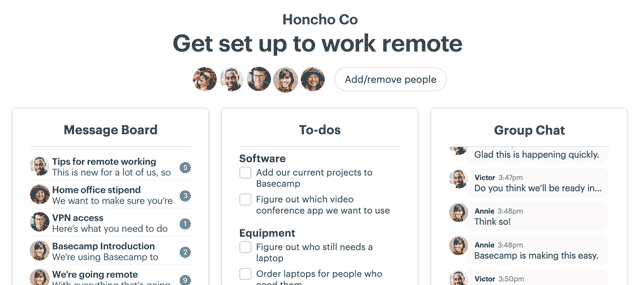

In 2005 I was hired by 37signals, and one of my first tasks was to devise a way to deploy Basecamp. Would you believe, it now ran on two servers, instead of one? (The horror! Oh, the complexity!) The “log in and svn up” deployment method no longer sufficed — at least, it was no longer sufficiently convenient.

So, in August of that year, I released “Switchtower”, a tool for automating deployment to multiple servers simultaneously. (Some months later, a trademark dispute caused me to rename the tool to “Capistrano”.) In an amazingly generous gesture, DHH and Jason Fried gave this tool to me. (Amazing, right?) It was mine, they said, to do with as I pleased.

For three years, Capistrano was my baby. I worked — mostly alone — to maintain it, to extend it, to enhance it. I loved it, and I loved the community of amazing developers and sysadmins that grew up around it. I loved helping to ease the pains that people were feeling with deployment and server administration. And I loved showing people how Capistrano could improve their lives.

It was a lot of fun.

And then, in August of 2008, Mark Imbriaco (37signals’ sysadmin at the time) and I had the opportunity to teach a series of seminars about Capistrano, showing people how to make the best use of the tool in a variety of situations. We were really excited. We signed contracts and started planning our curriculum, dollar signs in our eyes and heads full of dreams of teaching.

And then I mentioned the plan to DHH. His reaction was not what I had expected, at all. Instead of being excited for us, he expressed concern. How much time would this take away from our responsibilities at work? What were our priorities? Where I saw an opportunity to do what I love — teach! — he saw a conflict of interest.

He was right. He was absolutely right. In hindsight, this was something I should have thought to talk to him about from the start. But it never occurred to me, and David’s insistence that we not teach the seminars was like a bucket of ice water over my head. I felt like I had been punched in the gut. The metaphorical rug had been pulled out from under me.

I don’t fault David at all, and I even agree that he was right to do what he did. But at the time I felt immensely betrayed. Capistrano was supposed to be my baby! Why, then, had I just discovered a limit beyond which I was not allowed to take it?

My passion for Capistrano waned rapidly after that. All of my open source projects suffered. In just six months, I went from being rabidly passionate about my projects, to feeling nothing but exhaustion and frustration when I thought about them. What had once been a joy had become an obligation.

And in February of 2009, I walked away from them. I announced my resignation, effective immediately, from Capistrano, Net::SSH (and related libraries), and the SQLite3 bindings I’d written for Ruby. I just…walked away.

My blog languished as I went many months without posting anything at all. (I rallied briefly at the end of 2010 and wrote a series of posts about maze algorithms, but it was sadly temporary.) By September of 2011 I was done blogging, and walked away from that, too. In 2012 I stopped tweeting.

I was withdrawing, and I didn’t know why. I’m sure I had no idea what was happening to me. By 2013 I was struggling to be motivated for any programming task, including the work I was being paid to do. I began to be frightened by “what if’s”. I had four young kids. What was I supposed to do if I couldn’t work? What would happen to us?

I tried (unsuccessfully) to reach out to a psychiatrist. I even wrote a series of short stories — for myself only — in which I put myself in a psychiatrist’s office and tried to answer the questions I imagined they would put to me. (This was, surprisingly, extremely therapeutic, and I would recommend it to anyone. It was, however, not enough for me.)

Jason and David were hugely sympathetic and supportive. One of the perks of working at Basecamp is a paid month-long sabbatical every three years, and they let me take an extra one, to help me get on my feet. They let me work as the primary on-call programmer for three months straight, an opportunity that let me work at many small problems every day, instead of one or two longer (and potentially overwhelming) tasks.

In the end, though, none of it was enough. My productivity had dropped to a trickle, ten percent or less of what it had been six years before. I felt horrible, guilty every time I thought of the paycheck I was drawing for work I was struggling enormously to do.

To understand what it was like for me, consider this snippet of Ruby code. It contains a simple bug. Can you find it?

class Circle

attr_reader :radius

def initialize(radius)

@radius = radius

end

def circumference

2 * radius * Math::PI

end

def area

radius * radius + Math::PI

end

end

The definition of the area adds pi, instead of multiplying by it. It’s a bug that would take an experienced programmer a minute or less to find. But looking at code like that, I would see nothing but a wall of text. I would grow exhausted just trying to scan it.

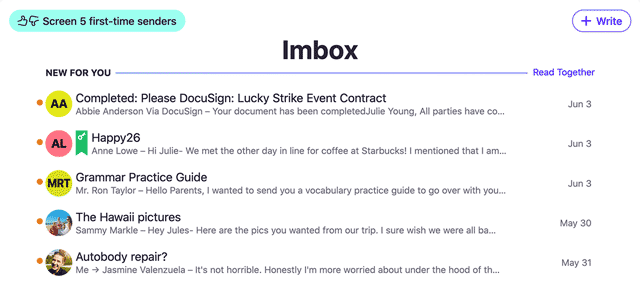

“I’ll just check my e-mail, first,” I’d say. Or, “I need fifteen minutes for some Kerbal Space Program, and then I’ll find that bug.”

(Only, anyone who’s ever played KSP knows that you can’t play just fifteen minutes of it. Suffice to say that I guiltily played a lot of KSP in 2013.)

I was paralyzed, emotionally and intellectually. The things I used to love to do, and which I used to do almost effortlessly, had become enormous, Sisyphean tasks. I couldn’t make myself care about work. Nothing could motivate me. I could not force myself to move beyond the mental blocks that sprang into existence at the very mention of computer programming.

My smile, as it were, was crippled. I was working with only half my heart, because the other half was frozen, palsied. My passion felt awkward, forced, and unnatural.

I was burned out.

Burnout is a dark place. Maybe especially in a male-dominated culture like software development, because male culture has this weird thing about showing weakness and sharing feelings. We don’t generally do either one easily.

When you’re burned out, you’re operating at a fraction of your capacity. Things that used to come easily are suddenly almost impossible. This does bad things to your self-image. It makes you feel weak. And it makes you feel ashamed of that weakness. “I should be able to do this!” you say. “I should be able to power through.”

And when you can’t, you feel even worse, and you spiral down, and down. Like someone with Bell’s palsy, embarrassed of their shattered smile, you turn inward. You try to hide your weakness. You put up a front, and conceal your broken self behind it.

The days turn to weeks, and the stress mounts. You hide yourself deeper. Your productivity falls further. People start to notice that something is wrong, but every well-intentioned question only adds to your shame.

“Why can’t I do this? I used to be able to do these things. I used to be strong…”

And so it goes, darker and deeper, until something breaks.

It came to a head at the beginning of April 2014. I spoke with Jason and David, explained my situation, and said goodbye to my friends at Basecamp. It was the hardest thing I’d ever had to do. Basecamp was my dream job. I loved the people. I loved the environment. But I just couldn’t do the work anymore.

Was that the end? Hardly. Burnout never has to be the end, and in my case, it’s really been more of a new beginning.

Ultimately, I took almost a full year off. For the first month, I don’t think I looked at my computer at all. My wife and I experimented with starting a creative arts studio for children. I carefully did some programming to support a novella I wrote about path-finding algorithms. And in September of 2014 I signed with Pragmatic Programmers to write a book about generating mazes.

Through it all, my wife and I talked about what we wanted to do. We tried a lot of different things. We imagined the future and where we wanted to be in it. We took stock of what we had, and what we could do, and tried to imagine creative ways to apply those resources.

And bit by bit, my passion for software started to come back. It was like a forest had burnt to ashes, and the little seedlings just needed some time, undisturbed, to start poking up through the blackened char. I could feel the first faint twitches that heralded the end of my paralysis.

By the time January rolled around, I realized that I had a few software projects going on the side. This was a new feeling! I hadn’t done software for fun in a long time. It felt good.

I felt…better. Stronger. Different.

I felt like — maybe — I was ready to try again.

Nervous — terrified! — I put together a pitch, and asked the world to hire me. With some advice from Jason Fried and Jeff Hardy, I eventually settled on a contracting gig, and I have been blissfully self-employed ever since.

Burnout was hard. It was not something I would have chosen for myself, and I wish I had known then the things that I know now. Probably I would still be working at Basecamp. My life would be very different than it is, I’m sure. But burnout happened, and I made it through, and I think I’m a better person for it.

I think I’m more balanced. I have a greater appreciation for what I lost during those darker times. My smiles are a bit wider, and a bit more sincere, and maybe a bit more touched with wonder.

Self-employment? This is not a place I ever imagined I would be. It’s not a place I ever imagined I would want to be.

But it is where I am now. And I’m smiling again.