Here’s one way to create more mental wriggle room for yourself in tough situations as a leader.

Before you figure out what to do, you must first figure out how to think as a leader.

But what if you’re not even sure what to think?

A direct report who’s well-liked by the team is underperforming, yet you can’t get a good read on the severity of it because this person is so popular. How do you figure out what’s truly going on? What do you tell your direct report? Should you consider finding someone else to fill the role?

Someone recently joined the leadership team who you’re pretty sure is going to be the downfall of the company, but no one else quite sees it yet. Are you even correct to think this? Do you say something if you are correct? If so, how exactly?

What to make of situations like these? It’s like someone put you in a box that you didn’t choose to be put in. You don’t have any wriggle room. Every option seems no-win.

So you hop down the Google rabbit hole, hoping there’s some handy blog post with “The Answer.” You vent or lament to your partner and friends.

And then you then do what many of us do: You ask for advice. You call up your old boss. A peer at your company who you respect. Someone you consider a mentor. You listen. You think it over some more. Then, you decide.

While advice-seeking is often the default path for thinking as a leader, I’ve learned that great leaders tend to be more deliberate in the kind of advice they seek.

I spoke with Joel Gascoigne, founder, and CEO of Buffer, on our podcast recently, and he revealed how he tends to think as a leader. Like many of us, when faced with a tough situation, he solicits advice from others. But Joel solicits conflicting advice, in particular. He told me:

“It’s great to have conflicting advice, because then you have to make your own decision. Then then you have to look within yourself and decide what is the right thing for this company, for the culture, and personally for yourself, as well.”

In short, Joel creates more wriggle room in that box by redefining what the constraints of that box are. By actively finding viewpoints different from your own – and different from the other advice you’re typically getting – you gain space, perspective, and context to make a decision on your own. When you don’t feel you have the room to think for yourself, you can create it.

Joel’s not alone in thinking this way, as a leader. When I interviewed Kathryn Minshew, founder, and CEO of The Muse, also on our podcast, she has a similar strategy for how she approaches important decisions that are hard to reverse – but with an even more specific methodology. Kathryn explained to me:

“I try and speak to at least three different people for any big decision or any area where it’s newer to me and I’m learning. In particular, it’s not just any three people,”

First, Kathryn will seek out advice from someone who is very similar to herself, saying, “I will specifically look for a woman CEO who potentially has had somewhat similar years of experience before starting a business.” This enables her to see how someone with a similar context has or might come to a certain conclusion.

Then, on the flip side, Kathryn will then “make sure that one of those people [she gets advice from] is someone whose experience is very different and whose perspective is likely to be very different.” For example, Kathryn described how she has a more collaborative leadership style, so she’ll gather out advice from someone who is more aggressive and hard-nosed in their approach.

Lastly, Kathryn will then seek out the opinion of someone who she believes has expertise in the area or something relevant to share.

When she does this – being rigorous about who and how she’s sourcing advice from – Kathryn notices how “it widens my understanding of what decisions are possible and what factors someone totally unlike me would consider.” For Kathryn, broadening her scope of opinions, each with their own particular reason for what value they might bring and the context they should be placed in, gives her the ability to create her own wriggle room and to think for herself as a leader.

This ability to hold two (or more!) opposing views at the same time – and to seek them out and be predisposed to them – is something that management scholar Roger L. Martin calls integrative thinking. His book on the subject, The Opposable Mind and his 2007 Harvard Business Review Article, “How Successful Leaders Think”, details the concept thoroughly. In both works and in his research, Martin asserts how great leaders tend to not assume their own model of reality is identical to reality itself.

Instead, great leaders look to test their own models, reframe them, and create new ones. When you seek out conflicting advice – be it in the more general way that Joel described or the more specific way that Kathryn described – you view the opposing models as hypotheses, rather than the truth. New possibilities peek their head out from the horizon line. A situation is no longer seen as “no-win.”

According to Martin, seeking conflicting advice is a critical part of thinking as a leader because it increases the amount of salient information you have at hand to make a decision. A person with conflicting advice is going to point out variables you might not have originally viewed as meaningful. They might also help you see the causal relationships that you didn’t realize existed before.

For instance, while your experience might tell you to shepherd an underperforming employee quickly and gracefully out of their current role, you might learn from a conflicting viewpoint that an underperforming employee might, in fact, be performing poorly because they are popular. They feel they contribute to the team in other ways and have no idea they’re in fact underperforming. Another conflicting viewpoint might suggest that this person may be underperforming because of you. Because this person was highly regarded by the team, you didn’t support this employee in the same way as you have others. You assumed their performance was up to par. Ouch. That’s a linkage you likely didn’t want to consider.

While hearing this conflicting advice might not be pleasant at the time (or ever), and while it can cause us to question the very foundation of our thinking – that’s the point. We can’t create more wriggle room in the box to think as a leader, if we’re not willing to, well, wriggle around.

To think as a leader, we must see the value in this conflicting advice, embrace the discomfort of breaking down our own beliefs, and know that we can indeed create more wriggle room in the boxes of our thinking if we want to.

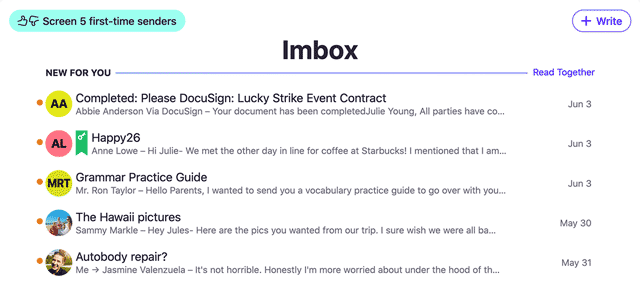

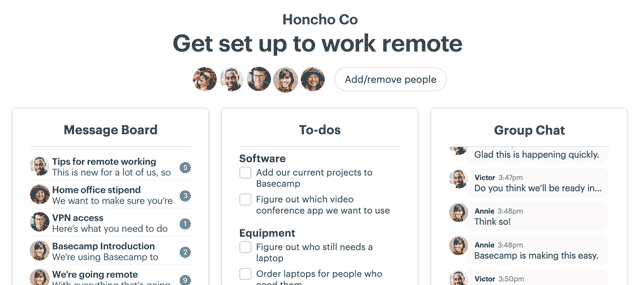

⚡️ Our software, Know Your Team, helps you nail the fundamentals of business and leadership: We help you run effective one-on-one meetings, get honest feedback, share team progress, and build team rapport. Try Know Your Team for free, yourself, today.

Claire is the CEO of Know Your Team – software that helps you avoid becoming a bad boss. Her company was spun-out of Basecamp back in 2014. If you were interested, you can read more of Claire’s writing on leadership on the Know Your Team blog.

Hi, Claire! I tend to lean on others – mentors & peers – for advice about situations like this. I also stick to a 72 hour rule, where I take at least 72 hours before making any major decisions so I have time to think it through and be sure I am not making a decision based on emotion. However, I do surpass the rule if the situation has an impact on safety of our employees or customers. Thanks for sharing!

Brilliant takeaway from this post: “When you seek out conflicting advice…you view the opposing models as hypotheses, rather than the truth.”

This makes sense to keep an open mind as a leader. It’s easier not to ask in that role. Similar to a company asking for customer feedback, you may not get the answer you want, but the answer you need.