I love print. I love the feeling of physically holding a book and turning its pages, or leafing through a magazine. As a former newspaper reporter, I never stopped marveling at how I could file an A1 story at 5 pm and by early the next morning, there it would be—my words and my byline, above the fold—on hundreds of thousands of papers landing on people’s doorsteps, a weighty tactile thing that had been physically printed and distributed at great expense.

But as a former newspaper reporter, I also have no delusions about the sorry state of print media. I lived through multiple rounds of layoffs and buyouts at my old job, and the real reason I still get the Chicago Tribune and New York Times in print form is because their Sunday editions are basically free with a digital subscription. I read most of my news online. Even in the digital-only world, high-quality sites have had their share of troubles, indicating that the challenges facing independent media are not just about format, but about finding that elusive mix of good content plus the right audience plus sustainable funding.

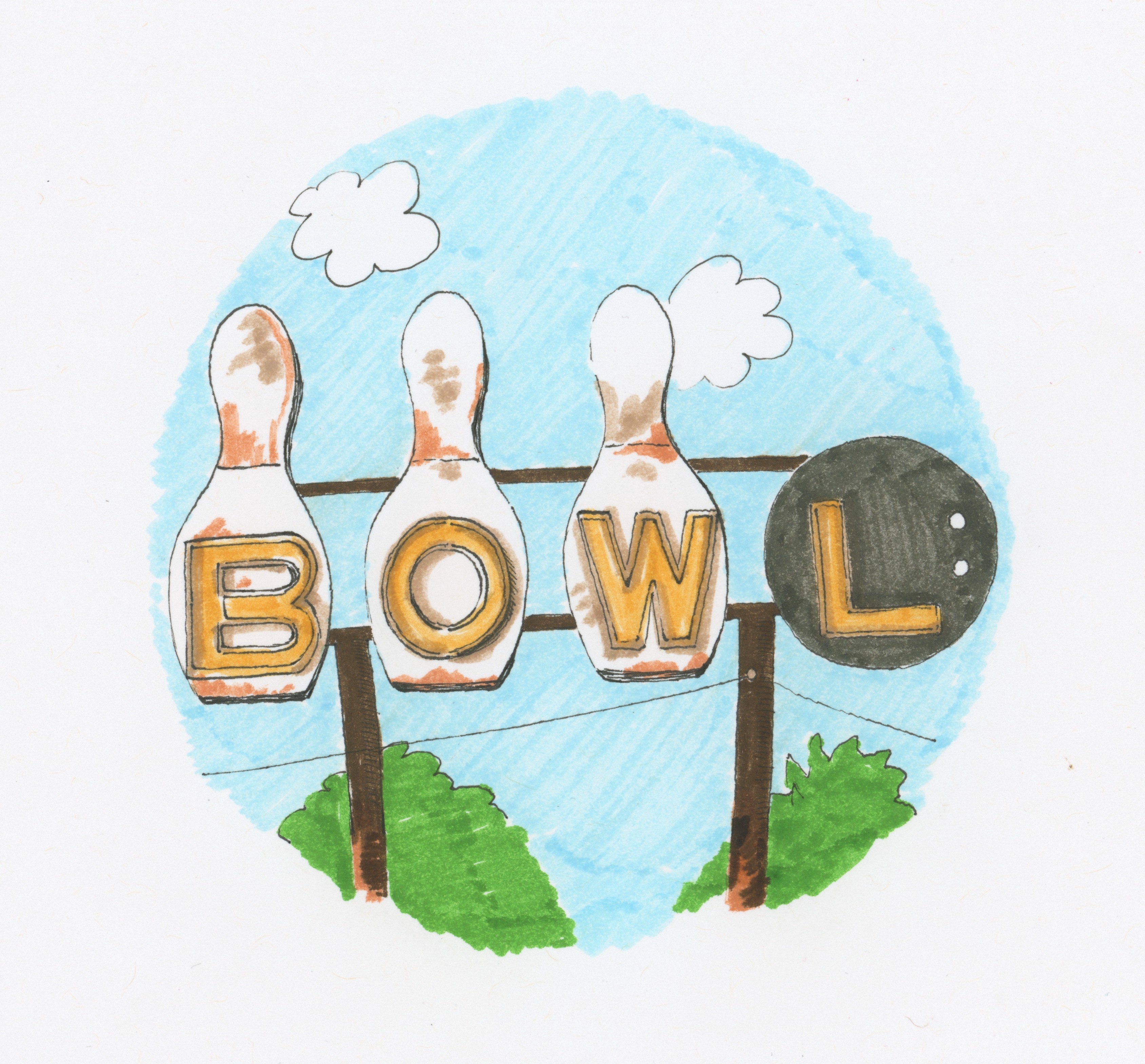

That’s why I was delighted to report a story for The Distance on Bowlers Journal International, the longest-running sports monthly in the United States. It is thriving in print—advertising is up! The magazine, founded in 1913 by a Chicago shoe salesman, has a remarkably loyal base of subscribers and advertisers. Of all the stories Bowlers Journal has told, the most enduring one is that of its own longevity and close relationship with its readers. Take a listen:

Transcript

WAILIN: Print media is dead. Right? We’ve witnessed the long, painful decline of newspapers and magazines and decried their inability to adapt to the digital age. Well, in certain corners of the publishing industry, print is very much alive.

KEITH: For print advertising, we’re already projecting to be up 10 percent. So you know what? The magazine world, it’s about the industries you serve. Now, if you’re broad-based consumer, that’s one thing. But you can’t assume—you can’t associate broad-based consumer publishing with what we do, which is niche-targeted publications. It’s a different world.

WAILIN: That’s Keith Hamilton, and his world is bowling. He’s the president of Luby Publishing, a company whose flagship title is Bowlers Journal International, the longest running sports monthly in the United States. It was founded in 1913, and it’s read by elite bowlers, pro shop operators and bowling center owners around the world. The circulation of Bowlers Journal has been steady at about 20,000 subscribers for the 34 years that Keith Hamilton has worked there.

KEITH: We know who our reader is. We meet our reader at the tournaments. We meet our readers at trade shows. We’re very intimate, probably one of the most intimate magazines with its readership that you can imagine.

WAILIN: The Bowlers Journal audience includes Hall of Fame players like Mike Aulby, who started reading the magazine as a teenager in the late seventies, started on the pro bowlers tour when he was just 18 and made the cover in 1985.

MIKE: You know, it’s kind of the go-to place for anything, especially the higher level of the sport, for us. We kind of kept tabs on it through there and you know, there’s one thing on the pro bowlers tour is you wanted to have a feature article in there because that was the spot where everybody in the industry would see it.

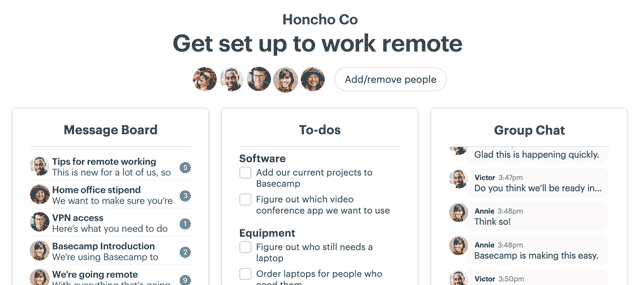

WAILIN: Welcome to The Distance, a podcast about long-running businesses. I’m Wailin Wong. On today’s show: the story of a print magazine and a beloved American pastime, both of which have survived Prohibition, the Great Depression, two world wars and more, all while retaining an incredibly loyal fan base. The Distance is a production of Basecamp. Introducing the new Basecamp Three. Basecamp is everything any team needs to stay on the same page about whatever they’re working on. Tasks, spur-of-the-moment conversations with coworkers, status updates, reports, documents and files all share one home. And now your first basecamp is completely free forever. Sign up at https://basecamp.com/thedistance.

KEITH: We publish Bowlers Journal, Bowling Center Management, Pro Shop Operator, Entertainment Center News, Billiards Digest. We can have 42 issues a year come through here.

WAILIN: That’s a lot.

KEITH: It is, because we’re very lean, as you probably noticed. We’ve got six people in the office.

WAILIN: Bowlers Journal has modest origins. It began as a weekly publication, founded by a 56-year-old shoe salesman and avid bowler in Chicago named Dave Luby. The first issue was eight pages long and the back cover had an ad from Brunswick, the bowling equipment manufacturer. The company has advertised on every back cover of Bowlers Journal since that very first issue in 1913.

KEITH: Yeah, Brunswick’s an amazing supporter of this company. Loyal, loyal as the day is long. It’s one of the longest relationships in any industry, I mean, 102 years with one advertiser is pretty good.

WAILIN: When Dave Luby died in 1925, the magazine passed to his son Mort. He was a World War I veteran who loved to bowl, drink and gamble, and he married a Hollywood-raised socialite who once played bridge with legendary actress Mary Pickford. Under Mort Luby’s watch, Bowlers Journal expanded to cover billiards but also lost its beer and whisky advertisers to Prohibition, and the magazine downsized from a weekly to a monthly. To keep money coming in, Mort Luby started a wire service that covered bowling tournaments for newspapers across the country. He also started a tournament, the Bowlers Journal Championships, which are still held today.

In 1967, Mort Luby died in his sleep on a Pullman car traveling home from a bowling industry event in Houston. His son, Mort Junior, took over Bowlers Journal at the age of 25. He still visits the office once a month.

KEITH: Great man. He set out a goal of life and man, he hit it. He hit every aspect of his life. So I got a lot of admiration for Mort. He basically set my life, my career path.

WAILIN: That career path started when Keith was just a college kid looking for a summer job. His sister knew someone who knew Mort Luby Junior and heard he needed help cleaning a Chicago townhouse he owned.

KEITH: Yeah, I remember like it was yesterday. Pulling up to that townhouse and seeing Mort Luby come out. He was driving a white Buick Park Avenue back then, and you knew right away this guy was something special just by his presence. It wasn’t that I had a desire to get into publishing—or bowling. It was just a job, then.

WAILIN: That cleaning job turned into a stint working in the Luby Publishing office during Keith’s breaks from college. He had been a high school athlete, playing football, basketball and baseball. He was not a bowler. His interest in the sport — and in the publishing business — would accumulate over time. Luby Publishing helped pay for his MBA program at Notre Dame, and Mort put Keith in charge of advertising when he graduated. As he started working full-time, he set his sights on a bigger opportunity.

KEITH: I saw a path to owning the company. Even when I was green with inexperience, I saw that you know what? Mort’s going to retire soon and there’s not really anybody here with the business acumen to step in and purchase the company.

WAILIN: Keith teamed up with Mike Panozzo, a colleague who worked on another Luby Publishing title, Billiards Digest, and had more editorial and journalism expertise. In the summer of 1992, they took Mort Luby Junior to Lawry’s, a Chicago restaurant famous for its prime rib. They wouldn’t officially take over Bowlers Journal until 1994, but it all started with that dinner.

KEITH: Mort was dropping some hints, you know, when I get outta here, when I get outta here, and Mike and I took him to dinner that night, told him we were interested in the company, and away it went. Now it was a long process because you know, we weren’t wealthy guys. Mort didn’t pay great (laughs). So it took probably two years. It was that type of process to get to a proper price and I tell you what. Sometimes, you just have to go through the process. If we went to Mort day one and said, Mort here’s the deal? He would have said no way. You have to go through the rigors of the back and the forth and the understanding of what this means. What this means from a tax perspective. My MBA? I learned that buying Luby Publishing. It wasn’t so much at Notre Dame. Sorry, Notre Dame. Great school. But it was definitely that process there, taught me more than I ever could have imagined.

WAILIN: Bowlers Journal has always been for the high-end bowler, the person who travels to tournaments and spends money on products. The magazine covers professional bowling competitions and provides detailed ball reviews, working with a testing center in Florida that can control variables like humidity and the amount of oil on a lane.

KEITH: Our readers, I’m not kidding, they can own up to six bowling balls because each ball performs differently on a certain lane pattern. They can have the same ball but drill it differently, you know where you put your thumbs? They can drill in another part of the ball. It has to do with the pin and the center of gravity and all that, stuff that I don’t know but I like to think I do.

WAILIN: Keith is being modest. His specialty may be on the business side of the magazine, but he’s picked up a lot of bowling expertise. It wasn’t until about 12 years ago, though, that he really started bowling. He got into it by joining a super tough league in the outskirts of Milwaukee and a more relaxed league in Chicago.

KEITH: At the good league, the challenging league, they talked about their bowling shoes. They talked about the pins. They talked about leagues. Everybody complained about the lane oil. The casual league, nobody talked about that stuff. They played their card games based on strikes and spares and they were eating pizza.

WAILIN: At the first game he bowled with the serious league in Milwaukee, he shot an 88.

KEITH: Some of the people knew me because of the magazine, so they expect me to be a good bowler. So I’m like apologizing for my bowling because I don’t want them to think the magazine is some hack, okay, because I don’t write instruction. I write about the business side of it or I don’t tell people how to bowl. So don’t judge the magazine because I stink. So I remember getting one of those few times in my life, we’ve all been there, you get that red-faced feeling permanating throughout your entire body from head to toe. That was me. It was awful.

WAILIN: But Keith improved, and for the last eight years, he’s averaged 170. Perhaps more importantly, joining that challenging league helped him better understand his audience. And knowing the Bowlers Journal readers is what’s helped Keith and Mike run the company. They know what their subscribers want to read and how to deliver that information better than anyone else.

KEITH: For example, we cover a bowling tournament. You gotta talk about what happened behind the scenes. Here’s what led to the shot that led to the shot that made him win the tournament. Or here’s what happened in the background. Here’s the friction that was going on in the crowd that you couldn’t see on TV. As long as you deliver original information, original content, you can be in print. Make no mistake about it. And I know our industry right now—it’s still print. We had a great online magazine, great digital magazine for two and a half years, but it just didn’t have the interest, so we had to can it.

WAILIN: This doesn’t mean that Bowlers Journal isn’t looking for ways to evolve. It publishes plenty of online content and has added a podcast featuring interviews with important figures in the sport. Keith thinks the magazine will look much different in ten years. He sees the way his 22-year-old son reads everything on his phone. And the bowling industry is undergoing significant change too.

KEITH: It’s going from a league-organized play base and it’s evolving into more of a nice Saturday night out entertainment. Now instead of bowling centers, they build what we call family entertainment centers, where bowling is an important, significant part of it, but it’s about the martini bar, it’s about the fancy lounge, it’s about the games, it’s about laser tag. It’s so much more than bowling.

WAILIN: These changes put Bowlers Journal at a bit of a crossroads. The growth of these family entertainment centers exposes more people to bowling who might not have otherwise visited a traditional bowling center. But casual bowlers don’t spend hundreds of dollars on balls and shoes, and those are the kinds of people that Bowlers Journal advertisers want to reach. I asked Mike Aulby, the Hall of Fame bowler you heard at the beginning of the episode, if he’d ever bought something after seeing it in Bowlers Journal. He remembered an ad for Ebonite, a bowling equipment company, that featured Earl Anthony, one of the sport’s all-time greats.

MIKE: And there was one where he would wear a trench coat with a Magnum Force bowling ball, and I have an orange bowling ball just because Earl threw it, so through those ads, so you bet.

WAILIN: The challenge for Keith and his staff is to cover the evolution of bowling as an industry and find ways to bring more casual bowlers into the fold, while still providing the kind of deep tournament coverage and ball reviews that will keep their core readers and advertisers coming back for the next hundred and two years.

KEITH: Obviously, we have a proven product, so there’s a lot of value for the 102. But you gotta earn it. You gotta improve. You gotta evolve. You gotta change. You gotta be hungry. You can’t expect business to keep going because you’ve been around for a hundred years.

WAILIN: Readers like Mike Aulby have seen their relationship with the magazine change over the decades. Mike no longer bowls competitively, but he owns a bowling center in Lafayette, Indiana, so he’s interested in reading about business trends. And there are subscribers like Fran Deken, who went from competing on the professional circuit to being a bowling writer, tournament director and high school coach. She started bowling at age 10 and reading Bowlers Journal shortly after that.

FRAN: I was 12 years old. My dad got us a subscription, my brother and myself, and we would argue over who got to read it first.

WAILIN: When Fran was growing up in the Chicago suburbs, she and her brother would drive to the city to attend tapings of a bowling television show, where they would look for the players they saw in the pages of Bowlers Journal. Fran ended up in the magazine herself. The first time was when she won a national intercollegiate tournament as a 20-year-old student at the University of Iowa.

FRAN: I love the Bowlers Journal all these years. Some decades have been better than others, but I save lots and lots of copies of it, although I’ve moved many times so I’ve had to unload some of them. But both of us, my husband and I, we always look forward to seeing what’s in the next month’s Bowlers Journal.

WAILIN: The magazine’s subscribers are remarkably loyal. Mike Aulby buys back issues on eBay and knows people who clip the vintage ads to frame as wall art. Keith Hamilton doesn’t take those readers — or his advertisers — for granted, even though he encourages his editorial staff not to back down from covering issues that might be controversial. He just asks his writers to be fair.

KEITH: Every day when that magazine goes out, three days later, I’m sitting there like waiting, I swear to God. After all these years I’ve been in the industry, you’re always waiting. Was there something in this magazine that ticked somebody off? But you know what? What they need to understand is, first of all, we have to do that. Because if we wrote a hundred percent of the time everything is great, it loses credibility. And the things that we’re writing about won’t have any, won’t matter.

WAILIN: Bowling doesn’t have the visibility of other sports. There are no household names like Tiger Woods. There are no glamorous pop culture references, like what The Color of Money did for billiards back in the 80s, although movies like Kingpin and The Big Lebowski are cult hits. And bowling isn’t an Olympic sport, despite intense lobbying efforts from the industry, including an unsuccessful bid to get it into the 2020 Summer Games in Tokyo. What bowling does have going for it is widespread consumer appeal, and that’s helped keep the sport alive.

KEITH: What’s great about bowling is that you can be male, you can be female, you can be child, you could be senior citizen. There are no barriers for you to bowl. Now, I can’t go out and play basketball anymore. I pull a hamstring just looking at the court. But I can bowl! Okay? I can bowl. My grandmother bowled up until 90. That’s the beauty of the sport, so that’s the reason that it appeals to everyone. And everybody has a good time bowling. Nobody comes back from bowling and says they had a bad time.

WAILIN: The Distance is produced by Shaun Hildner and me, Wailin Wong. Our illustrations are done by Nate Otto. I send out a newsletter every two weeks where I round up other interesting stories about long-running businesses. To sign up for that, visit https://thedistance.com and scroll down to the bottom to enter your email. The Distance is a production of Basecamp, the leading app for keeping teams on the same page about whatever they’re working on. Your first Basecamp is completely free forever. Try the brand new Basecamp Three for yourself at https://basecamp.com/thedistance.com.