Otto Wiegel founded Wiegel Tool Works the day before the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. This year, his three grandchildren mark the manufacturing company’s 75th anniversary. The family business, which specializes in precision metal stamping, has survived succession issues and dislocations in the global economy to become somewhat of a rare species: A midwestern American manufacturer in growth mode.

Transcript

(Sound of machinery)

WAILIN WONG: This is the sound of heavy metal. Or more specifically, heavy metal stampers. They’re massive presses clocking in at 200 tons, 400 tons and 450 tons. The largest machine, the 450-ton press, mostly makes a specific copper part that goes into car transmissions. The finished piece fits in your hand, but the machine that makes it is so big it’s rooted five feet underground in a pit that took 38 cement trucks to fill.

RYAN WIEGEL: The reason why we got the 450 is because of the bed size. We never need the tonnage. We might go to a 150 to 200 to 250 tons on a 450-ton press. That’s not much at all. We needed the bed size. The complexity of the tools was required to produce a part, it’ll fit in the size of your hand, but in order to produce the part, you need multiple stages and once you put those multiple stages, you’re gonna need that bed length in order to produce the part.

WAILIN: That’s Ryan Wiegel, who along with his brother and sister own Wiegel Tool Works. Their grandfather, a German immigrant, founded the company on December 6th, 1941, a day before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. That uncertain beginning was the first of many events that would threaten the existence of Wiegel Tool Works over the next 75 years, including family succession issues and the most recent recession. Here’s Erica Wiegel.

ERICA WIEGEL: We wanted to get in the recession and get out of it with all our employees. We wanted them to maintain their households, their payments, their cars, their bills and just because the economy was suffering and we were suffering, we wanted to make sure that we came out as well as they did too.

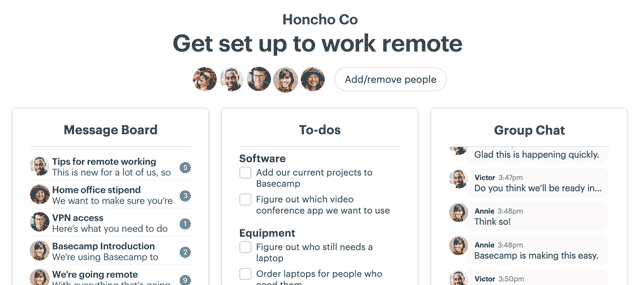

WAILIN: Welcome to The Distance, a podcast about long-running businesses. I’m Wailin Wong. On today’s show, how the Wiegels’ strict financial discipline helped them pursue their vision of what American manufacturing looks like in a post-recession economy. The Distance is a production of Basecamp. Basecamp is the better way to run your business. It’s an app for communicating with people and organizing projects and work. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by email, chat and meetings, give Basecamp a try. Sign up for a 30-day free trial at basecamp.com/thedistance.

Wiegel Tool Works is based in Wood Dale, Illinois and specializes in precision metal stamping. You can think of metal stamping like punching a shape out of a piece of paper. But instead of paper, the Wiegels use ribbons of copper or brass that are wound on flat spools the size of wagon wheels. And the end result isn’t a simple flat shape like a circle or a heart, but a piece with a complex topography of holes and ridges and peaks. These metal pieces go into things like automobiles, exhaust fans and kitchen appliances. Here’s Aaron Wiegel.

AARON WIEGEL: We’re certainly not a commodity. I mean, stamping right-angle brackets is just not in our DNA over here. We have very, very sophisticated tools. We do take on the tough projects and because of that, we’re not labeled as a commodity and that’s why they’re forced to come to a very select few, you know, vendors that can do what we do.

WAILIN: When Aaron and Ryan’s grandfather, Otto Wiegel, started the company, it was a tool and die maker. It made tools for metal stamping but didn’t do any stamping itself. In 1968, Otto suffered a stroke while his only child, Martin, was serving in Vietnam with the U.S. Navy. Martin was honorably discharged so he could return home and help run the family business. During the 42 years Martin was in charge, Wiegel Tool Works started stamping. It continued making tools, but just for its own stamping jobs.

RYAN: The stamping was where all the money was, so when our accountant joined up with my father back in ‘94, he says, “Marty, you gotta stop building tools for the outside and you’ve gotta focus on stamping,” and from that day forward, we’ve been having a big push for that. Had we not done that today, we would never be the size and potentially would not be in business today because it’s a very, very competitive business.

WAILIN: Otto Wiegel died before any of his grandchildren were born. But his presence loomed large at the factory where the three Wiegel kids played laser tag, rode a dirt bike around the parking lot, sorted metal washers and eventually got to learn how the business worked. They understood from early on how they and the company depended on each other for their well-being. Here’s Erica Wiegel.

ERICA: It would be our birthday time and my dad would ask us, “You know, you’re gonna be 16, do you want a brand new Mustang fully loaded, whatever you want? Or do you want a Green Bruderer machine?” And we decided that we wanted the Bruderer ’cause that machine would make us better, make us money, and it could employ more people and just expand our business.

WAILIN: This emphasis on financial discipline pervaded much of the Wiegels’ upbringing. Martin’s favorite phrase is “cash is king.”

ERICA: We also went on vacations where my dad would give us a certain amount of money for lunchtime and whether we wanted to spend it all on the first day of vacation or let it drag out for the whole seven days, it was our choice, but it was also a way of learning money management.

WAILIN: Otto Wiegel died in 1973. By that time, Martin was running the company, but his mother, Otto’s widow, retained ultimate financial control. When she passed away in 1993, her death set off a chain of events that tested the company’s survival.

RYAN: My dad was really strapped financially. He could not um purchase capital equipment and once ultimately my grandmother passed away and he inherited this money, it was a challenge for him because the transfer did not go well. And because of it, we really struggled for quite a few years.

WAILIN: Ryan is talking about the estate tax, which is a tax on property that transfers from a deceased person to their heirs. The federal estate tax is a contentious political issue, with its opponents calling it the death tax because of how it can debilitate small businesses and farms. Here’s Aaron.

AARON: It is a job and company killer. That second generation taking over is already at a major disadvantage because they have to come up with 55% of what they’re inheriting, which in our line of work, I mean, to pay off 55% of the equity that we just inherited, it’s all tied up in, in capital equipment and buildings and it’s not liquid in cash. So to come up with that money is very difficult and it sets you back for years.

ERICA: The most important thing is that my dad looks at everybody here as their family, their extended family, and if my family was not able to pay off the death taxes, my dad would have to look at 35 people in the face and tell them that they don’t have a job anymore. Now that we’re 170 people, we wouldn’t have the face to tell 170 people because of a death tax, that we can’t support your job anymore.

RYAN: That’s why my father started planning really as soon as my grandmother died and he did not want to have that burden on us, the third generation.

WAILIN: When Martin Wiegel started doing his succession and financial planning, Aaron was only in eighth grade and it was too early to know whether he or one of his siblings would take over the company. But things quickly fell into place. Aaron and Erica studied engineering at the same college, while Ryan spent a high school summer working for an equipment dealer and studied communications. They all wanted to join the family business. In 2010, each of the three siblings became part owners of Wiegel Tool Works. Aaron is the president, Ryan is project coordinator, and Erica sits on the board while running a different metal stamping company that she bought with her own money in 2015.

AARON: Splitting this company between one owner to three owners, which most historical companies when that happens, it usually becomes a disaster because it’s a three-headed monster and if you don’t have the checks and balances and the hierarchy, it could really uh blow up in your face.

ERICA: We grew into this our whole life, so when we did transfer and take over the company, it was nothing new for us. The only thing was it was new for the employees. They didn’t even know that we were owners until months later, we said, “Oh by the way, we are the new owners,” and that’s how well the transition went.

WAILIN: The difficult thing during that period wasn’t managing the transition from Martin to his three children. It was making sure that Wiegel Tool Works could get through the recession. The company’s fortunes were closely tied to those of American car companies, which ended up needing a federal bailout.

AARON: My dad’s been by our side the entire time including today. He doesn’t work full time, but he comes in and does a lot of advising for us. Had he not been there during that time, we would not be sitting here talking right now. Some of the decision making that went on during that time period, I would never have made those calls and would have had the strength to do it because I just thought it was too extreme in some cases, but he certainly made the right decisions to cut things where they needed to be cut and just survive because if you waited a day, it might have been a day too late. It was just survival mode.

WAILIN: The advantage that Wiegel Tool Works had was that it was debt free, and it had a reputation of paying suppliers on time and hitting its production deadlines for customers. So the thinking was that as long as the company could stay afloat, it would outlast competitors with weaker balance sheets and larger debt burdens. But the atmosphere was still uncertain and terrifying. So the Wiegels took an extra step. They printed out their bank statements and brought them to meetings with customers.

AARON: They weren’t allowed to take them, but they were allowed to review them. We were showing that we were a debt-free company, that we were stable and also we had a succession plan already written in place and all lined up, which we executed the following year. They wanted assurance because it was a very, very scary time. I remember running the business and at the same time, when I had time left over, I went on the floor and ran machines. I was running around with forklifts. I mean, you did what you had to do to survive. So you know, visiting customers and seeing the look and scare on their faces that we’re gonna try to award you this business, yet we don’t even know if we’re gonna be open tomorrow, is a very scary uh thought.

WAILIN: I asked Aaron when he felt like the business and the economy had turned a corner. He had an instant response down to the month.

AARON: It was October 2009 (laughs). The government came out with the Cash for Clunkers uh law and that spurred a lot of new purchases of cars when they submitted their old cars, so we were heavily involved with in the American automotive world, the GMs, the Fords, the Chryslers.

WAILIN: Wiegel Tool Works still makes a lot of parts for the automotive industry, but in the last 16 to 17 months, it’s been diversifying into other sectors like LED lighting and construction. Another major priority for the short term is diversifying geographically, which for the Wiegels means opening a second plant in Mexico.

AARON: When my grandfather was running the business, I mean, everything was real local. Today’s markets are real global. We’re supplying parts directly to Japan, to Europe, to Mexico. Um, currently, 45 percent of our products are shipped to Mexico and now we’re seeing a lot of pressure to expand to these areas so that our customers have our capabilities and our production right in their backyard. Customers today just simply do not want to pay for the logistics. They don’t wanna have um waste in their lines, meaning everything has to be lean, so if you are shipping from the United States to Mexico, let’s just say, that’s a five to 10 day transit that is running the clock and taking up their liquid um money, so they want to be right next door. They want to be producing parts at that time and not have a lot of inventory, to keep their money in the bank, I guess. It’s a risk, but a risk that we have to take, given that the global competition and the global customers we’re dealing with today, I mean, my grandfather and my dad’s customers just don’t exist anymore and all those guys were all in the city of Chicago or in the general area. That’s just not the way it’s played anymore.

WAILIN: The nature of the company’s work has changed dramatically too. There’s more automation and robots and real-time monitoring. One stamper has two high-res cameras that inspect parts and ejects defective ones with a blast of air. Aaron says he wants more people to understand how American manufacturing, or at least his corner of it, has evolved into a high-tech and forward-thinking industry.

AARON: If I wasn’t in this industry, I don’t know how I’d even begin to describe what manufacturing would be outside of what I’ve seen in movies. That’s one of the reasons why we’re trying to promote manufacturing as much as possible and try to get rid of that stigmatism that lurks over us, that it’s just a dirty oily grungy type of environment where, you know, you could lose a hand at any moment. You know, you’re not getting oily, you’re not getting dirty, you’re almost at a computer all day long programming these machines to do a lot of this stuff.

WAILIN: Aaron always has to be looking ahead, whether it’s toward a big equipment purchase, opening a Mexican factory or training new generations of tool and die makers. Regardless of what’s next, he wants to be around to make those decisions and protect the family legacy.

AARON: There’s not a day that goes by I don’t get calls or I don’t get a letter from somebody saying that there’s some big overseas company or something local that that wants to acquire you. Now, have we looked at some of these deals? Sure, I mean some of the stuff that we looked at, it’s tough to turn it down but at the same time, we have a legacy here and we’ve got a longstanding tradition and no deal would ever be made unless it’s in the best interest of the family and the company. We’ve got a long rich history and we’ve got a growth trend that’s been currently happening and at this point, uh, there’s really no need to do that unless, uh, it’s going to enhance the overall business—which we would still be involved in.

WAILIN: The Distance is produced by Shaun Hildner and me, Wailin Wong. Our illustrations are by Nate Otto. Thanks to ErikBison and whydoineedanickname1234567890 for your five-star reviews on iTunes. If you’d like to have your amusingly long user name read on the air, head on over to iTunes and leave us a review. The Distance is a production of Basecamp, the app for helping small business owners stay in control of projects and reduce email clutter. Try Basecamp free for 30 days at basecamp.com/thedistance.