Santa Fe, New Mexico is home to around 200 art galleries. Even in this thriving art scene, Nedra Matteucci’s gallery stands out. The 44-year-old gallery, which she bought in 1988, is housed in an adobe compound spanning two acres, and the business takes a grounded approach to fine art. If visiting the Nedra Matteucci Galleries feels like you’re stepping into someone’s home, it’s because Nedra, a New Mexico native who got her start selling paintings on the road, has made approachability part of the overall experience.

Transcript

WAILIN: Three decades ago, when Nedra Matteucci and her husband bought their first-ever piece of art, it was a big step. They had been visiting galleries together since they were dating, but this was their first purchase.

NEDRA: It was a lithograph for $125 and we asked if it came framed, so we have come quite a ways from that. I didn’t grow up with paintings in my home. I grew up in southeastern New Mexico, uh, small farming town south of Roswell. We raised cotton and alfalfa and since then, it’s become a dairy community. And that southeastern part of the state is oil and gas too so yes, we had a little Texas twang, but it was New Mexico twang (laughs).

WAILIN: Today Nedra is an established art collector, dealer and gallery owner, but she’s kept that New Mexico twang. It’s an important part of the business she runs in Santa Fe, one of the country’s biggest art markets. A century ago, artists came to this town, drawn by the beautiful light, rugged landscape and unique cultural mix of the American southwest. They helped establish an artistic tradition that’s distinctive from the coasts. And the Nedra Matteucci Galleries, which first opened in 1972 and is housed in a historic adobe compound on two acres, stands out even among Santa Fe’s two hundred some galleries, thanks to its history, size and the way it makes fine art accessible. Here’s Dustin Belyeu, who’s been the director at Nedra Matteucci Galleries for 12 years.

DUSTIN: We don’t want people to be intimidated at the gallery. We want them to come in here and really have a good time. We encourage our sales staff and people to stand up and say “Hi, how can I help you? Where are you visiting from?” The other thing is we like anybody to be able to walk away with something from their experience here. Not everybody can afford a $100,000 piece of art, not everybody can afford a $1,000 piece of art, but most people can maybe afford a bracelet that’s $250 or a little piece of pottery that’s $75. And it’s important for Nedra, especially from her background and how she started in this business, for anybody to be able to have that experience and walk away with a nice piece of art from an institution, a place like this.

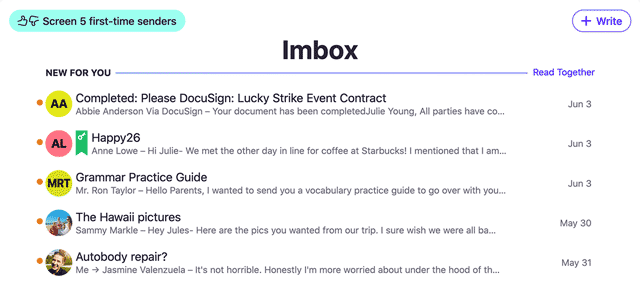

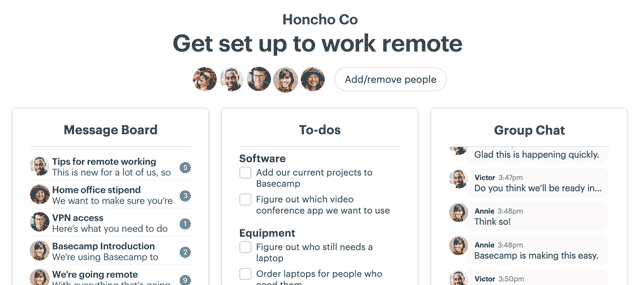

WAILIN: Welcome to The Distance, a podcast about long-running businesses and the people behind them. I’m Wailin Wong. On today’s show, how Nedra Matteucci has maintained her down-to-earth approach to fine art over a career spanning more than 30 years. The Distance is brought to you by Basecamp. The brand new Basecamp 3 helps small business owners stay in control of projects and reduce email clutter. Tasks, spur of the moment conversations with coworkers, status updates, reports, documents and files all share one home. And now your first basecamp is completely free forever. Sign up at basecamp.com/thedistance.

NEDRA: It’s a different world, you know. Bankers don’t understand it. It’s not like any other business there is. There’s not a set mark-up. There’s not set prices, you know, each object is a piece of art and it’s handled differently, sold differently. So it’s really a complicated business to explain, I’d say, but you learn every day.

WAILIN: In the early eighties, Nedra was a collector. Her first purchases were works on paper because they were affordable. Then she and her husband got interested in pieces by contemporary Native American artists and later on, historic works by artists who came to New Mexico in the late 1800s. Within a few years, their walls began to fill up. And that’s how she shifted to the other side of the transaction.

NEDRA: I had wall-to-ceiling paintings and then I’d find something I liked better, so I’d have to sell something else, started selling to girls I played tennis with and I’d gone to a boarding school in El Paso and I’d go to El Paso and sell and met people and sell on the road and worked with a small museum in El Paso exhibiting paintings, and that’s how I started representing some of the living artists, by taking their paintings to this show in El Paso, a museum show.

WAILIN: It’s easy to think of selling art as an ultra-rarefied line of work, a gallery owner meeting with clients in pristine, museum-like spaces. And there’s certainly an element of that at Nedra’s gallery. On the day we talked, she was wearing a tailored tweed skirt suit and we sat at a table adorned with a Fernando Botero sculpture selling for six figures. The front room has a small Georgia O’Keeffe painting of plums in a dish priced at $850,000. But in those early, scrappier days, Nedra was loading her car with paintings and sculptures and driving the four hours from Albuquerque to El Paso.

NEDRA: I was taking a bunch down one time and one was a stone sculpture and my husband says — he had to put in the car — and he says, “Geez, do you have to sell stone?” (Laughs)

WAILIN: Nedra’s burgeoning career as an itinerant art dealer eventually brought her to Santa Fe and its thriving art scene — and one gallery in particular, owned by a well-known art dealer named Forrest Fenn, who in 1972 had taken a run-down property and built it into a large compound.

NEDRA: I drove up here and the first time the gallery was very intimidating, so I drove back to Albuquerque. My husband said no you go back out there, and so I tried to sell him a painting and he said, “Well, why don’t you sell some of mine?”

WAILIN: That was a big break for Nedra. Forrest Fenn consigned paintings to her and she would sell them, and that turned into a part-time job at the gallery where she studied auction records and immersed herself in the art business. She eventually opened her own small gallery in 1986. And then, two years later, Nedra got a life-changing surprise.

NEDRA: My husband came home and said he bought this gallery (laughs). So he bought me a very big job. I cried every day for a month, but fortunately if I hadn’t worked here, I wouldn’t know how it operated, and I had that advantage for this.

WAILIN: The Forrest Fenn gallery had been on the market for a few years, and Nedra and her husband were longtime admirers of the building and the grounds. The space couldn’t be more different than the austere, modern white-walled boxes you might associate with art galleries. Here, at what’s now called the Nedra Matteucci Galleries, you ramble through different rooms of a sprawling adobe estate and make your way to a backyard garden with a goldfish pond and large sculptures, like an elephant on its hind legs spraying real water into the air. There’s an extensive research library, a courtyard built around a gnarly old tree, and guest quarters with a sauna and hot tub. As a teenager, Dustin Belyeu lived in an apartment above the gallery when his mother, Nedra’s sister, moved to Santa Fe to run the gallery’s finances.

NEDRA: This building, parts are over 200 years old, some of it’s 50 years old, some 70. The back room at one time had even been a foundry. It’s adobe. It’s more like I bought an institution. We have two guest houses for clients, friends. The artists stay there. It’s not just a gallery. You have a big operation.

WAILIN: Overnight visitors stay on the site for free, and the gallery staff can hang specific works in the guest house so that potential buyers get a feel for what it’s like to live with those pieces. This same idea flows throughout the gallery, parts of which have an informal, lived-in quality to it. It’s a kind of studied casualness, and part of the subtle salesmanship the gallery uses to put the art in its best light. Dustin, who worked at the New York auction house Sotheby’s for three years before joining his aunt’s gallery, decides which pieces go where, and how they’re displayed. One room used to be part of Forrest Fenn’s family home but is now part of the gallery and dedicated to the work of living artists, with some pieces resting on the floor and leaned up against furniture.

DUSTIN: That’s what Forrest Fenn did when he built this place. Instead of building it to look like every other art gallery, he wanted it to look like a home, so that you could visualize what these pieces of art could look like in your home. And then Nedra’s carried on that tradition a hundred percent and it’s one of the biggest challenges with this space, as big as it is, to hang each room uniquely but to have a feel with the art that they all fit together.

WAILIN: Nedra is especially proud of the sculpture garden. It was Forrest Fenn’s private yard when he owned the gallery, and Nedra wanted a space to display and sell very large pieces. Her interest in representing sculpture artists started when she opened her first, small gallery in 1986. She knew of an artist named Dan Ostermiller, an American known for his large-scale animal sculptures.

NEDRA: He had two big rabbits I saw him making at a big outdoor sculpture show and I called him and I said, “Could I represent you? I’d love to have those two big rabbits in front of my gallery on the corner to draw people in ’cause I’m not in a great location.” He said, “I would love to, but the problem is I can’t afford to cast them.” I said, “How much does that cost?” And he told me and I said, “I’ll find the money, so put them through the foundry,” and so we’ve grown together for over 30 years. He was my first sculptor I had.

WAILIN: Today, the sculpture garden at the Nedra Matteucci Galleries is filled with Dan Ostermiller’s pieces, and visitors are encouraged to touch them. The garden is perhaps where the idea of approachable art, which is present all through the gallery, is truly put into practice.

DUSTIN: We have one artist who lost his vision in Vietnam, a blind sculptor named Michael Naranjo, and he helped us get to the point where we want kids, we want people to engage with this art. Not a hands-off, like “Don’t touch that”, that’s something we try not to say here ever because he talked about when he was a kid, going to museums and galleries, and always being told, “Don’t touch that,” and it discouraged him and it made him not want to be an artist or around art. He wants to do the opposite, help people engage with the art, have a connection to it, beyond something that’s just there to look at. We take that a step further with most of the sculptures. We’re happy to have kids touch ’em, uh especially the big ones outside that can’t, you know, fall off a table or something and I think parents really enjoy it, you know? Because they walk in and start to do that “Don’t touch this” and we’re like “No, go to the garden, let the kids, you know, engage with these things and have fun with them.”

WAILIN: As a gallery owner and art dealer, Nedra serves as a bridge between artists and buyers, and to be successful, it’s important to cultivate long term relationships with both groups. At this point in Nedra’s career, there are more living artists who want the gallery to represent them than there is wall space. She estimates that she turns down about a dozen artists every month. Finding customers, especially new ones who have never bought art before, is a different challenge.

NEDRA: We’ve tried advertising in younger magazines ’cause when we first bought the gallery, it was already an older, established group of collectors and you have to get always find new and younger ones. And when you find someone under 40 buying, you’re just excited. That’s one reason we did more living artists at a price range where everybody can afford something and start collecting. We have living artists that you can buy a painting, you know, for $1,000, to $70,000 for instance, and you know, then you go into the deceased area, you’re looking at starting at the low end $25,000, I would say, you know, up to over a million. There’s not everybody that can do that. But we have such a good variety of paintings.

WAILIN: Nedra’s gallery has other advantages too: its history with Forrest Fenn and its unique space, which makes it a destination for the tourists that visit Santa Fe. But Nedra and her staff can’t just coast on reputation. Every sale counts, and prices can vary dramatically with shifts in the broader art market. Remember that small Georgia O’Keeffe painting selling for $850,000? That might seem high for a piece that’s only 7 by 9 inches, but an O’Keeffe just sold for $12.9 million at a Christie’s auction in May. That kind of milestone helps justify the price tag on the O’Keeffe that Nedra is selling — which, by the way, has an interested buyer. You can tell because there’s an orange dot sticker on the little sign next to the painting.

DUSTIN: It’s totally unpredictable and it’s seasonal. The summer season is when you’re busy, you know, you’re gonna sell more art than in the middle of the winter or the early spring in New Mexico, which isn’t the best time of year to be here. There’s no actual numbers we have out there we try to hit. We try to sell as much art as we can every single month and if you cover the bills that month and make some money, that’s fabulous. Some months you do fall a little short, but, um, it’s just a daily business that we every single day reach out to people, talk to people in the gallery, try to sell art.

NEDRA: Getting good paintings, historical paintings, is the hardest. There’s fewer paintings coming on the market and you have tremendous competition now is your auctions. There’s a lot of small auctions, plus the big auction houses, so we’re all going for the same pie. And you just, uh, do your best and we’re, uh, very honest. We’re very fast payers and we’re frank, and I think that is one quality that we have that stands out and has been carried on through the years.

WAILIN: Today, Nedra is thinking about selling the big compound and scaling down. This is part of a long-term plan she’s been working on. In 2002, she acquired a gallery called Morningstar, which specializes in Native American antiquities. She closed her original gallery in 2010 after a 24-year run. Her goal is to eventually consolidate everything at Morningstar, which is much smaller than the old Forrest Fenn property and happens to be adjacent to her house in Santa Fe.

NEDRA: I’m already excited about the plans I have for it and to go forward that way. So I feel like it’s not giving up something, I’m gaining another phase of my life. I know exactly what I want to do with it. And we’ll still have room for outdoor sculpture because I have property behind me and I have about an acre of my own house I can break off for the gallery to use too. I have this all planned, so I’m not worried about it in the least. The part I’m worried about is how long it’ll take us to get this all out of here (laughs). And where we’re gonna put everything.

WAILIN: The Distance is produced by Shaun Hildner and me, Wailin Wong. Our illustrations are done by Nate Otto. Thanks to Nat Chakeres for his help with this story. You can find our show at thedistance.com, on iTunes, where we would love it if you rated and reviewed us, and on Google Play Music. The Distance is a production of Basecamp, the app for helping small business owners stay in control of projects and reduce email clutter. Your first Basecamp is completely free forever. Try the brand new Basecamp Three for yourself at basecamp.com/thedistance.